When you walk into a pharmacy and pick up a generic version of your prescription drug, you’re probably not thinking about the legal battles that made that possible. But behind every low-cost pill is a complex web of laws, lawsuits, and corporate strategies designed to either protect or block competition. In the U.S., antitrust laws are the main tool used to keep generic drug markets fair - and they’re under constant pressure from companies trying to delay cheaper alternatives from reaching patients.

How the Hatch-Waxman Act Created the Modern Generic Market

The foundation of today’s generic drug system wasn’t built by a free market. It was designed by Congress in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. Named after its sponsors, Senators Orrin Hatch and Henry Waxman, this law struck a delicate balance: it gave brand-name drug makers extra patent protection to reward innovation, while creating a faster, cheaper path for generics to enter the market. The key was the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which lets generic companies skip expensive clinical trials if they prove their drug is the same as the brand-name version. But the real game-changer was the 180-day exclusivity window for the first generic company to challenge a patent. That’s not a reward - it’s a weapon. The first generic to file a Paragraph IV certification (claiming a patent is invalid or not infringed) gets a head start on the market. In theory, this creates competition fast. In practice, it’s become a target for manipulation.Pay-for-Delay: When Brands Pay Generics to Stay Off the Market

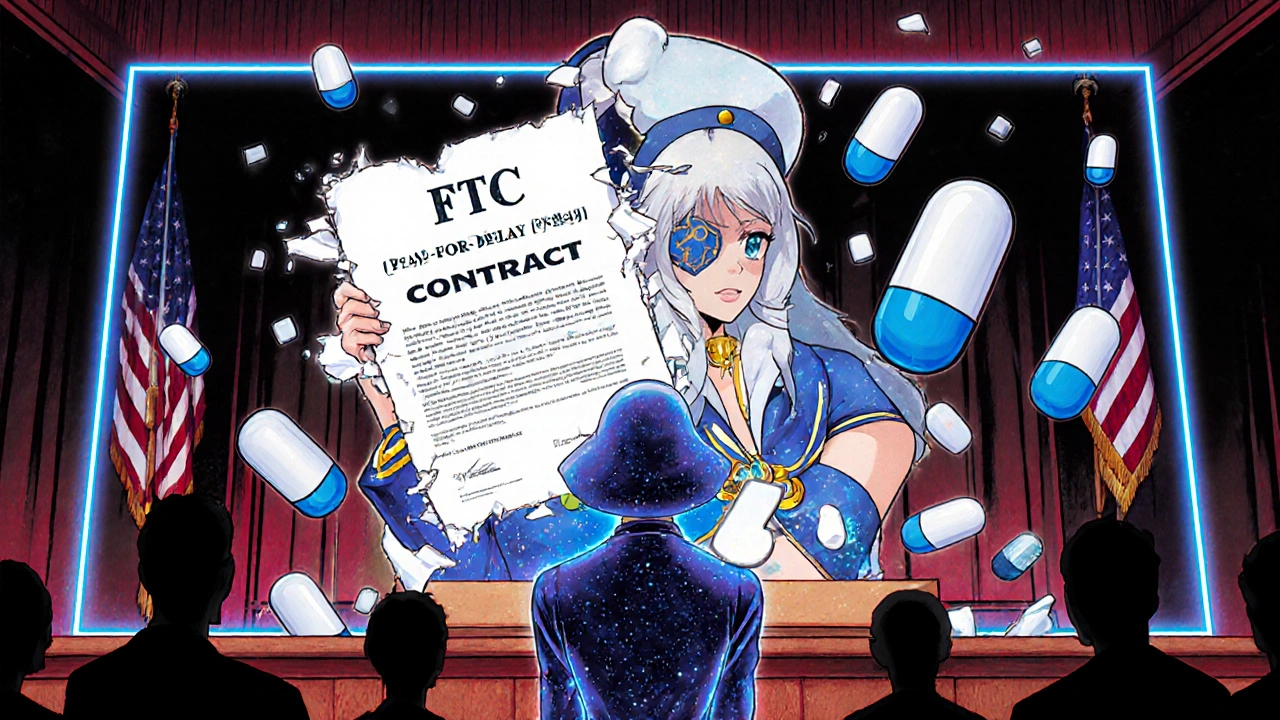

Here’s where things get shady. Sometimes, instead of fighting in court, a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to delay its launch. These deals, called pay-for-delay agreements, look like settlements - but they’re really bribes. The brand keeps its monopoly. The generic gets cash. And patients pay more. The FTC has been fighting these deals for years. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these payments could violate antitrust law if they’re large and unexplained. That didn’t stop them. Between 2000 and 2023, the FTC pursued 18 pay-for-delay cases, with settlements totaling over $1.2 billion. One of the biggest came in 2023, when Gilead Sciences paid $246.8 million to settle allegations it blocked generic versions of its HIV drug Truvada. These aren’t just legal issues - they’re health issues. When a generic drug finally enters the market, prices drop by at least 20% in the first year. With five generic competitors, prices can fall by 85%. That’s why the FTC estimates that between 2005 and 2014, generic drugs saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. In 2012 alone, savings hit $217 billion. Delaying entry by even a few months costs billions - and lives.Product Hopping and Other Tactics to Block Competition

Branded drug companies don’t always need to pay off competitors. Sometimes, they just change the product. This is called product hopping. A company slightly alters a drug - maybe changes the pill shape, adds a coating, or switches from a tablet to a capsule - right before the patent expires. Then they market the new version as “better,” even if it’s not clinically different. The most famous example is AstraZeneca and its acid reflux drugs. When Prilosec’s patent was about to expire, the company launched Nexium - a slightly modified version. They spent millions advertising Nexium as superior, even though the active ingredient was nearly identical. Pharmacists and doctors started prescribing it instead of the generic Prilosec. The result? Generic entry was delayed, and prices stayed high. Courts have been mixed on whether this is illegal. In one case, Walgreen Co v. AstraZeneca, the court dismissed the claim because AstraZeneca didn’t block generics - they just made their own product more appealing. But the FTC still calls it anti-competitive. And in 2023, they filed a new case against Teva Pharmaceuticals for allegedly using fake citizen petitions to delay generic versions of its multiple sclerosis drug Copaxone. The case is still pending.

Sham Petitions, Orange Book Abuse, and Disparagement

Another tactic? Filing sham citizen petitions with the FDA. These aren’t real concerns about safety - they’re legal delays. A company submits a petition claiming a generic drug is unsafe or ineffective, knowing the FDA will take months to respond. While the petition is pending, the generic can’t be approved. The FTC has called this a “gaming” of the system. Then there’s the Orange Book - the FDA’s list of patents for brand-name drugs. Companies are supposed to list only valid, enforceable patents. But some add patents that don’t even cover the drug’s active ingredient, just the packaging or dosage form. This blocks generics from entering. In 2003, the FTC sued Bristol-Myers Squibb for listing patents that had nothing to do with the actual drug, just to block competition. And it’s not just about patents. Some companies spread false information about generics - claiming they cause more side effects, aren’t as effective, or have unknown risks. This is called disparagement. It’s not illegal per se, but it’s a powerful tool to scare doctors and patients away from cheaper options. A 2020 study showed this tactic reduces generic use even after legal barriers are gone.Global Differences: How Europe and China Handle Generic Competition

The U.S. isn’t alone in this fight. The European Commission has taken a different approach. Instead of focusing mostly on pay-for-delay, they target regulatory manipulation. In one case, a company withdrew its marketing authorization in several countries just to prevent generics from entering. In others, they made misleading claims to patent offices to extend protection. The EU estimates these delays cost European consumers €11.9 billion a year. China’s approach is even more aggressive. In January 2025, they released new Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector that identify five “hardcore restrictions” as automatic violations: price fixing, output limits, market division, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. By Q1 2025, they’d already penalized six cases - five involved price fixing through text messages, apps, and even algorithms. China’s regulators are now using AI to monitor pricing trends across online pharmacies. If a group of generic makers suddenly raise prices in sync, the system flags it. That’s a big shift - from reacting to lawsuits to preventing collusion before it happens.Why This Matters to Real People

All of this isn’t just legal theory. It’s about whether someone can afford their insulin, their blood pressure pill, or their antidepressant. A 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 29% of U.S. adults skipped or cut their medication because of cost. That’s not laziness. That’s a system that lets drug prices stay high long after patents expire. The savings from generics are real. The Congressional Budget Office says generic drugs cost 30% to 90% less than brand-name versions. That’s why the FTC says 90% of all U.S. prescriptions are now for generics. But if companies keep finding ways to delay entry - through pay-for-delay, product hopping, sham petitions, or misinformation - those savings vanish. And it’s not just about money. When a patient can’t afford their meds, they end up in the ER. Their condition worsens. Their family suffers. The health system pays more. The cycle continues.What’s Next? The Fight Isn’t Over

The FTC is pushing for stronger rules. They want to make pay-for-delay deals harder to hide. They’re calling for more transparency in Orange Book listings. They want to ban product hopping when it’s clearly designed to block generics. And they’re watching China’s AI-driven enforcement closely. But change is slow. Courts still debate what counts as “unreasonable.” Regulators are underfunded. And pharmaceutical companies have billions to spend on lawyers and lobbyists. The real question isn’t whether antitrust laws work - they do. The question is whether we’ll let them be used the way they were meant to: to protect patients, not profits.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drug approval in the U.S. It lets generic manufacturers use the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process to prove their drug is equivalent to a brand-name version without repeating costly clinical trials. In exchange, it gives brand-name companies extended patent protection. The law also gives the first generic company to challenge a patent 180 days of market exclusivity - a powerful incentive to enter the market quickly.

What are pay-for-delay agreements and why are they illegal?

Pay-for-delay agreements happen when a brand-name drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. These deals are illegal under U.S. antitrust law if they involve large, unexplained payments that prevent competition. The Supreme Court ruled in 2013 (FTC v. Actavis) that such payments can violate antitrust rules because they protect monopolies instead of resolving legitimate patent disputes.

How do generic drugs lower prescription drug costs?

Generic drugs lower costs by introducing competition. Once the first generic enters, prices typically drop by at least 20% within a year. With five or more generic competitors, prices can fall by up to 85%. Between 2005 and 2014, generic drugs saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generics cost 30% to 90% less than brand-name drugs.

What is product hopping and is it illegal?

Product hopping is when a brand-name company makes a minor change to a drug - like switching from a tablet to a capsule - right before its patent expires, then markets the new version as superior. While not always illegal, courts have ruled it anti-competitive when the goal is to block generic entry. The FTC considers it a tactic to manipulate the market and has targeted cases like AstraZeneca’s Prilosec to Nexium switch.

How do antitrust laws differ between the U.S., EU, and China?

The U.S. focuses on pay-for-delay deals and sham petitions. The EU targets regulatory manipulation, like withdrawing marketing authorizations to block generics. China, since 2025, has taken a stricter approach, banning five hardcore restrictions including price fixing and using AI to detect collusion. China has already penalized six cases in 2025, mostly for price fixing via messaging apps and algorithms.

Andrea Johnston

November 18, 2025 AT 23:06This is the exact reason I can't afford my antidepressants. I don't care about corporate patents - I care about breathing. If a company can pay a competitor to keep life-saving drugs expensive, we're not in a market, we're in a dystopian nightmare.

And don't get me started on how pharmacies still push the brand-name version even when the generic is cheaper. It's not about patient care - it's about kickbacks and greed.

Scott Macfadyen

November 19, 2025 AT 14:24Man, I used to work in a pharmacy. Saw this shit up close. Patients crying because they had to choose between insulin and rent. Meanwhile, the pharma execs are on their yachts in the Caribbean. No wonder people are angry.

Chloe Sevigny

November 20, 2025 AT 18:00The structural inefficiencies inherent in the U.S. pharmaceutical regulatory framework are not merely market failures - they are systemic rent-seeking behaviors enabled by legislative capture. The Hatch-Waxman Act, while ostensibly a compromise, functioned as a legalized cartel mechanism, wherein patent litigation was commodified into a revenue stream rather than a judicial safeguard.

Pay-for-delay agreements represent a textbook case of per se antitrust violation under the Rule of Reason, yet judicial deference to corporate legal maneuvering has rendered enforcement toothless. The FTC’s reactive posture is not incompetence - it is institutional acquiescence.

Denise Cauchon

November 20, 2025 AT 22:47Canada’s system is way better. We don’t let these greedy bastards play games. If you want to make money off medicine, you better make it affordable - or get the hell out.

And don’t even get me started on how the U.S. lets Big Pharma bribe politicians. It’s disgusting. We’re not a third-world country - we’re supposed to be the leader. But nope, we’re just the world’s pharmacy slave.

Also, why do Americans still think ‘free market’ means ‘let corporations murder people for profit’? I swear, your democracy is broken.

Victoria Malloy

November 21, 2025 AT 13:14I’m so glad someone finally laid this out clearly. It’s not just about money - it’s about dignity. People shouldn’t have to choose between their health and their survival. I hope more people see this and start demanding change.

Alex Czartoryski

November 22, 2025 AT 14:22Product hopping? That’s like switching from a Ford F-150 to a Ford F-150 with new seats and calling it a new model. Then charging $50k more. Genius. Or just… evil. Either way, it’s a scam.

And the Orange Book? That’s not a list - it’s a cheat code for monopolies. The FDA’s supposed to be the gatekeeper, but they’re basically letting pharma write their own rules.

Gizela Cardoso

November 24, 2025 AT 08:28China using AI to catch price-fixing? That’s actually kind of impressive. We’ve got lawyers and lobbyists playing chess while they’re playing checkers. Maybe we should stop pretending regulation is about fairness and start treating it like a tech problem.

Erica Lundy

November 24, 2025 AT 10:05It is imperative to recognize that the legal architecture governing pharmaceutical competition in the United States has been systematically subverted by private interests seeking to maximize shareholder value at the expense of public welfare. The judicial interpretation of antitrust statutes has increasingly favored corporate autonomy over consumer protection, resulting in a de facto legalization of monopolistic conduct under the guise of patent law.

Moreover, the absence of meaningful regulatory oversight at the FDA, coupled with the institutional inertia of federal agencies, renders the current enforcement paradigm fundamentally inadequate. Structural reform - not incremental litigation - is required.

Kevin Jones

November 25, 2025 AT 19:55Pay-for-delay = corporate bribery. Product hopping = legal fraud. Sham petitions = regulatory trolling. And the FTC? They’re out here filing lawsuits like it’s a game of whack-a-mole while the whole damn board is rigged.

China’s using AI to catch price-fixing. We’re still arguing whether a pill coating counts as ‘innovation.’ We’ve lost.

Premanka Goswami

November 26, 2025 AT 01:23Who really controls the FDA? Who owns the patents? Who funds the Supreme Court justices? This isn’t about drugs - it’s about the New World Order. Big Pharma, the Fed, the WHO - they’re all connected. They want you dependent. They want you medicated. They want you too sick to protest.

And don’t tell me this is about ‘innovation.’ Innovation is when you cure cancer. This is just profit laundering with pills.

Alexis Paredes Gallego

November 27, 2025 AT 05:07Wait - you mean the government lets companies pay other companies to NOT sell cheaper medicine? That’s not capitalism. That’s fascism with a pharmacy license. And the fact that people are shocked? You’ve been brainwashed. This is how the system was designed - to make you poor and obedient.

And now you’re mad because you can’t afford insulin? Congrats. You’re exactly what they wanted.

Richard Couron

November 29, 2025 AT 04:11YEAH AND THE CHINESE ARE USING AI TO MONITOR PRICES?? THAT'S COMMUNIST SOCIALISM!! THEY'RE TRACKING EVERYONE'S MEDS NOW?? WHO'S GOING TO BE NEXT? YOUR BLOOD PRESSURE??

THEY'RE GONNA MAKE YOU TAKE A DNA TEST BEFORE YOU CAN BUY ASPIRIN. THIS IS THE END OF FREEDOM. WE'RE BEING TURNED INTO LAB RATS FOR BIG PHARMA AND THE CCP. I SAW A VIDEO ON TRUTHSOCIAL - THEY'RE PUTTING MICROCHIPS IN THE PILLS NOW. I'M NOT TAKING ANYTHING FROM A PHARMACY EVER AGAIN.